Underwater fibre optic cables rarely come into view – as long as there is no failure. Meanwhile, they carry almost all the intercontinental Internet traffic. We are talking about a network with a length of more than 1.4 million kilometres with hundreds of access points, through which up to 97-98% of global data exchange passes. Any failure in this system instantly goes beyond a “technical problem” and turns into an economic and operational crisis.

This has become particularly evident in recent years. Large-scale incidents have shown how vulnerable global connectivity is and how expensive the infrastructure compromises made during the design and planning stages are.

Failure as a Systemic Phenomenon, not an Exception

On average, there are about 200-210 damages to underwater cables per year in the world. The vast majority of them are not related to sabotage but to the human factor and natural causes: anchors of ships, fishing activities, storms, seismic activity, wear and tear of equipment. Up to 30% of all incidents are directly related to anchor dragging.

The problem is compounded by the fact that a single incident often affects several cables at once. There have been cases where one ship damaged lines for hundreds of kilometres, creating multiple points of failure at the same time. In such scenarios, classical redundancy mechanisms work worse than expected on paper.

The average recovery time after a serious injury is weeks and often approaches 40 days. The reasons are the limited number of specialised repair vessels, difficult logistics, weather conditions and political restrictions in certain regions.

Cascading Failures and Domino Effect

Submarine cables are not just data transportation but the basis for cloud platforms, financial systems, distributed computing, API interactions, and cross-border traffic. When one route fails, traffic is redirected, signal latency increases, bandwidth decreases, and service degradation begins.

In major incidents, situations were recorded where up to 25% of regional Internet traffic was unavailable or seriously degraded. In some countries, the drop in connectivity reached 85-90%. At the same time, there was no formal “shutdown”; – the systems continued to work, but with a sharp increase in delays, timeouts and errors.

For businesses, this means not just a slowdown but direct losses. Downtime of critical systems is estimated at thousands of units per minute. In large-scale cases, the cumulative economic damage was estimated in the billions. Financial flows, medical services, production chains, and remote management systems are becoming dependent on physical infrastructure, which is rarely mentioned in strategic documents.

A Single Point of Failure Due to Poor Planning

A common feature of many incidents is the concentration of traffic and the lack of infrastructural diversity. One route, one point of access to the shore, one region – and the failure becomes systemic. This is a classic example of a single point of failure, created not because of a lack of technology, but because of design decisions and savings on “invisible” elements.

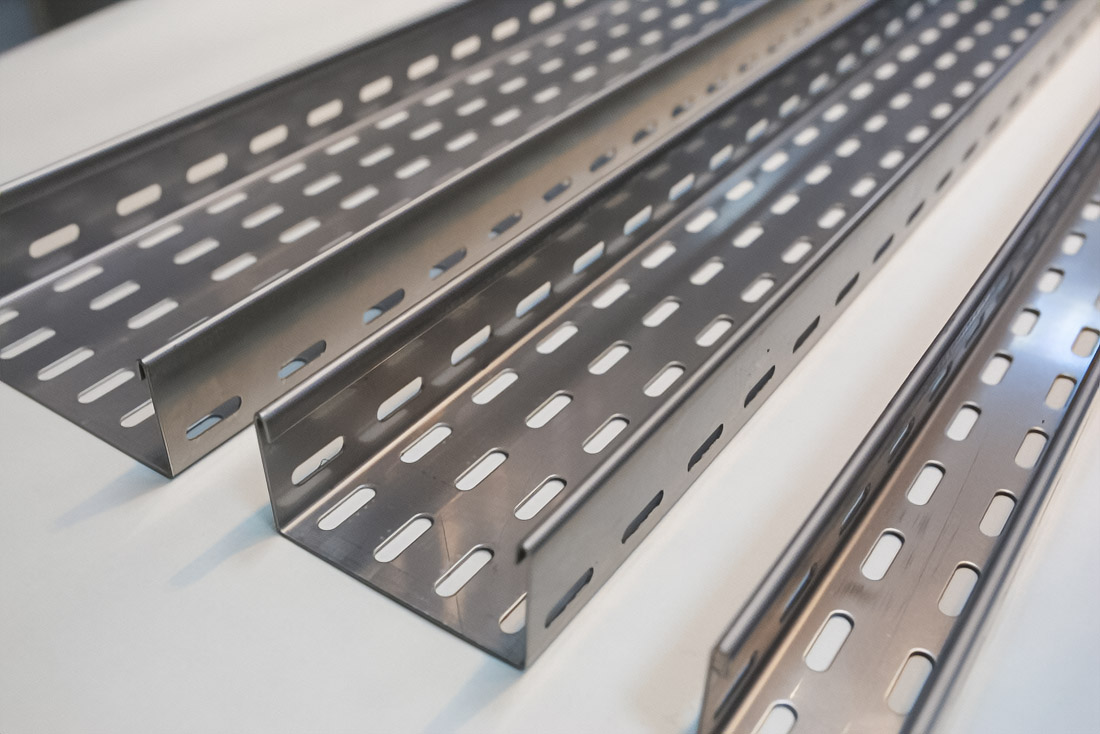

The same logic can be traced in terrestrial projects: cable routes are designed at the end, installation and operation specialists are connected too late, budgets are cut, and flexibility and scaling are postponed “for later”. In data centres and large facilities, this frequently leads to overloaded cable tray UAE installations, poor segregation of power and fibre, and the use of containment systems that were never intended for future scaling.As a result, there are overloaded cable trays, bending radius violations, mixing of power and optical lines, difficult maintenance and a high risk of failures.

When structured cabling is treated as secondary, flexibility disappears quickly. Improvised containment, undersized trays, and the absence of modular solutions such as slotted channel systems make upgrades slow, risky, and expensive. Maintenance becomes complex, access is restricted, and the probability of accidental damage increases.

The history of large infrastructure and IT projects shows the same pattern. Miscalculations in planning, lack of monitoring of the real status, unrealistic goals, underestimation of risks and the human factor led to budget overruns by 2-3 times and delays for years. Formally, the projects continued to exist, but in fact, they turned into a source of technical debt.

Resilience is Not the Absence of Failures

The key conclusion of recent years is that fault tolerance does not mean “never breaks”. We are talking about the ability of the system to survive a failure with minimal consequences. Practice shows that countries and regions with developed geographical redundancy, multiple routes, local caching and distributed data processing recover faster and lose less.

In some cases, connectivity was maintained through land routes, local hosting, and maintaining traffic within the region. Where there were no such mechanisms, the failure of one cable led to an almost complete loss of access.

At the company level, this is directly related to business continuity. Reserving routes, diversifying suppliers, monitoring delays and degradation, understanding the real time of repairs – all this is becoming not an exotic network, but a part of risk management.

Why the Problem Will Only Grow

The volume of data is increasing, latency requirements are becoming tougher, and dependence on cross-border services is deepening. At the same time, the physical infrastructure is developing more slowly than the logical one. The number of cables is growing, but the repair capacity and transparency of the infrastructure are lagging behind.

An additional factor is geographical “bottlenecks”, where dozens of lines pass through limited sea corridors. The damage at such a point is automatically scaled to several regions.

At the same time, most of the attention is still focused on applications, platforms and services, while the physical layer remains secondary. This creates the illusion of reliability, which is destroyed at the first serious incident.

Underwater cables and the cable infrastructure as a whole are not the background but the foundation. Failures here are not rare anomalies but represent a regular risk with predictable causes and consequences. Ignoring this fact leads to cascading failures, economic losses, and loss of trust.

Sustainability does not begin with emergency response but with design solutions: infrastructural diversity, elimination of single points of failure, early involvement of specialists and honest risk assessment. In a world where data has become a critical resource, the physical ways of its transmission are no longer secondary.

Basketball fan, vegan, drummer, International Swiss style practitioner and holistic designer. Producing at the sweet spot between beauty and programing to craft an inspiring, compelling and authentic brand narrative. I’m a designer and this is my work.